The rose-cut diamond takes the form of a pyramidal or hemispherical gem covered all over in small facets. Also called ‘rosette,’ the rose cut earned its name from the fanciful comparison of its faceted dome to an opening rosebud. Up until the rise of the brilliant cut, rose-cut diamonds were the most popular.

Time to read:

Table of Contents

Origin of the Rose-Cut Diamond

While undoubtedly among the oldest cuts for diamonds, the exact origin of the rosette is rather uncertain. The year, or century for that matter, when the rose diamond came to Europe is in doubt. Some say that the rosette was in use since 1520, while others suppose that the pattern came in the middle of the 1600s. The latter seems the more plausible when we consider that the prominent authors Kentmann and De Boot — writing about diamond’s cuts in 1562 and 1600 respectively — knew nothing of the existence of a rose-cut diamond.

This article is part of the series

DIAMOND CUTS

The first allusion to a rosette in Europe came from De Laet, writing in 1647, when the Dutch lapidist from Antwerp spoke of the lasques or thin diamonds:

“They are reduced into the outline of a rose, or a heart, or a triangle, or a shield, and are diversified, but only on the surface, with several triangles or lozenges, which gives them remarkable effect …”

Rose-Cut Diamonds of India

The uncertainty over the advent of a rose-cut diamond in Europe seems to point to a foreign origin. Tavernier, who travelled to India from 1631 to 1668, found the rosette and similar cuts already of wide use in the subcontinent. Of the twenty largest Indian diamonds that the French merchant sold to King Louis XIV, five were variants of the rose-cut diamond, the rest being mostly tables. Tavernier also found the greater part of Emperor Aurungzeb’s diamonds to be roses.

The rosette as a design was quite agreeable to Indian lapidaries, whose high regard for diamond’s weight held them back from grinding away so much of its volume. The rose cut evidently emerged as a fancy style of cutting aimed at bringing out the diamond’s innate brilliance and keeping the most of its precious weight at the same time. Even in Tavernier’s visit to India, the native lapidaries already fashioned diamonds into perfect briolettes, which are basically roses joined base-to-base.

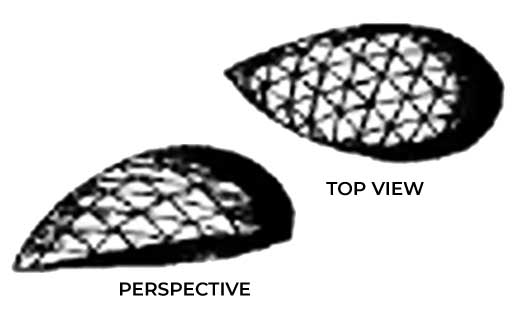

Another form of the rose-cut diamond that the Indian cutters produced is the pear-shaped rosette, which resembles a briolette halved down the middle. This teardrop rosette corresponds in shape to the round European rosette, both being bounded by a broad flat plane underneath. The only difference lies in the outline, which in the pear gem tapers to a point on one end, which thus looks like the tip of a falling drop of water.

In fact, a rounded Indian diamond bearing small facets was, as Tavernier states, “ordinarily called ‘a rose.’” Thus, all the Mughal-shaped gems, including the Kohinoor, must have gone under this name.

Rose-Cut Diamonds in Europe

The European rosette itself must have stemmed from the Mughal fashion of cutting. The round rose cut in particular was rather characteristic of most of the large diamonds cut in India. The Orloff, for example, before it became the largest diamond among Russia’s crown jewels, likewise emerged from India already in the shape of a rose-cut diamond.

© Elkan Wijnberg, published with permission

Thus, as King says of the European rosette, “In all likelihood, it was an Italian improvement on the Indian fashion.” European cutters may have learned rose-cutting from Indian lapidaries, and built on the technique until it became their own distinctive style. King cited the fact that it was a Venetian living in India, his name Hortensio Borgis, who fashioned the Great Mogul into a remarkably rose-cut diamond, which, as Tavernier saw in 1665, displayed the small triangular facets that became characteristic of European faceting. Borgis even bungled the cutting of the largest of rough diamonds, for which the emperor of India severely punished him.

Indeed, the rosette, as Streeter claims, may well have been in use from as early as 1520, yet the rose-cut diamonds received their cut not in Europe, but in India. The only distinct patterns that European cutters executed in this century were, as Kentmann relates, the point and the table. Hence, as some authors claim, the Florentine Diamond and the Sancy were the first rosettes that came to Europe, yet neither may have actually received their cuts in the continent. Both may have been among those pear-shaped rose diamonds that Indian lapidaries skillfully produced.

Characteristics the Rose-Cut Diamond

Like a cabochon yet facetted all over, the rose-cut diamond has all its facets on the upper side only, while the underside is simply flat, resulting in a broad plane forming the base of the gem. A feature that distinguishes the rose cut from older forms of cutting is the shape of its facets, which, as De Laet noted, came in “triangles or lozenges.” These triangles and rhombs became characteristic of European faceting.

In fact, it was the application of these facets upon the single cut that gave birth to the brilliant form, later to dominate European cutting.

Shapes of the Rose-Cut Diamond

The convex profile of the European rose-cut diamond varies between pyramidal and rounded. What determine the roundness of the rose diamond’s crown are the number of facets, their shapes and arrangement. The angle at which the central facets meet particularly decides the pointedness of the dome.

Owing to the relative ease in cutting, rose-cut diamonds most often received a round outline. When properly executed, the round rosette also produced the most brilliance, which must have accounted for the prevalence of this shape.

While the rosette’s outline as seen from the top is typically round, this shape frequently also bore an oval or pear outline. Like the Sancy Diamond, some of the rose-cut diamonds Tavernier brought home from India carried a pear-shaped outline. The shield-shaped diamonds De Laet mentioned must have also taken a similar outline. In fact, the rosette was susceptible to any form, including the heart and triangle of the 1600s. Lapidaries availed of a desired shape particularly when the rough stone approximated to it. Indeed, the shape of the rough stone was an important consideration in deciding the outline of the rose-cut diamond, which ideally entailed the least amount of waste, leading to the production of the biggest gem out of a raw crystal.

Effectiveness of the Rose-Cut Diamond

Unlike the old European cuts, the rose-cut diamond well displays the stone’s innate brilliance. Since the light that enters a rose diamond bounces off the flat underside and shines through the other side of the gem, the rosette permits a relatively superior display of the diamond’s brightness and luster. Such brightness was undoubtedly what De Laet meant when he spoke of the “remarkable effect” that the rosette’s facets brought out. “The rose-cut diamond is very lively,” indeed remarked Emanuel from the 1800s, “and makes a great display at a small cost …”

Efficiency of the Rose-Cut Diamond

Besides a brightness then unrivaled, what made the rosette so attractive to diamond-cutters was the relatively smaller volume of raw material required, and accordingly the minimal weight lost during cutting. On this account, the rosette proved to be the most suitable shape for thin stones. These include the flat triangular crystal called ‘veiny,’ which lapidaries generally split and cut into rose-cut diamonds. Small fragments cleft off larger diamonds likewise produced rosettes. De Laet, indeed, back in 1647 wrote of how cutters applied the rosette’s facets to the lasques, and how “by this means the stones make a show of much greater weight than they really possess.”

If too small for the true rosette, diamonds received just twelve facets, or even eight or six. By these fewer facets, rose-cut diamonds came into the market under the name ‘Antwerp roses.’ Dutch lapidaries, however, excelled in cutting miniscule rose diamonds without diminishing the number of facets or their arrangement. Thus, small rosettes from Holland often surprisingly bore all 24 facets, even though they were so tiny that 1,500 of them put together weighed less than a carat. Known as ‘piece-roses,’ such gems were exceedingly small that one’s breath blew them away. With thin edges that are quite liable to break, these minute roses required great care in handling.

Before the advent of the brilliant cut, large well-proportioned rough stones also popularly assumed the shape of a rose-cut diamond. The rosette is particularly suited to rough stones of a circular shape, since cutters can carve the facets of the hemispherical gem from a rounded crystal with greater efficiency.

Varieties of the Rose-Cut Diamond

With a diversity in the shapes of facets, their number and arrangement, the rose-cut diamond comes in a rather wide range of varieties, some of which readily identified the place whence the polished diamonds came.

Dutch Rose Diamond

Unless otherwise specified, the rose cut refers to the Dutch rosette. When people spoke of the ‘regular rosette’ or the ‘true rosette,’ they particularly meant the Dutch variety. Diamonds from the city of Amsterdam came in this shape, hence the word ‘Dutch rosette,’ as well as the alternate names ‘Amsterdam rosette’ and ‘Holland rosette.’

What distinguishes the Dutch from other rose cuts is its high pyramidal dome. As a rule, the Dutch rosette is half as deep as it is wide, thus conforming to the ideal proportion that brings the most brilliance out of the rose-cut diamond. When such convention was adhered to, much of the light that enters a rosette bounces off the flat base and shines through the other side toward the observer.

A rose diamond shaped in the Dutch fashion culminates in a point formed by six triangular facets. This apex is the so-called star, and its facets the star facets. The base of each star facet squarely meet the base of another triangular facet below, thus forming a rhomb, which was probably the “lozenge” that De Laet of mid-1600s referred to. In this manner the hexagonal star at the center develops into a full six-rayed star, with the lower tip of each ray touching a corner of the rose-cut diamond. For the rest of the gem’s surface, the triangular style of faceting continues, resulting in the so-called ‘cross facets,’ whose bases together make up the edges of the rosette.

All in all, the Dutch rosette has 24 facets: six in the star at the center and eighteen in the surrounding teeth. The facets remarkably come together in a way that their edges constitute straight lines crisscrossing the breadth of the rose-cut diamond.

Brabant Rosette

The Brabant rosette is similar to the Dutch rosette in the arrangement of its facets, but not in their angles and hence the proportions of the entire rose-cut diamond.

The central facets of the Brabant rose diamond form a much lower pyramid, resulting in a rather rounded crown. The cross facets around the edges also incline in a somewhat steeper angle, thus decidedly giving the rose-cut diamond a hemispherical profile. The result is a rosette too shallow for its breadth and with the upper facets coming closer to parallelism with the base.

Given this substandard shape and proportion, more light escapes through the back of the rose-cut diamond instead of reflecting toward the top. Hence, the Brabant rosette is far less effective than the Dutch rosette. It thus comes as no surprise that the Brabant rosette was much less used than its Dutch counterpart, and consequently fell from fashion early on.

The Brabant rosette apparently originated from Antwerp, when the latter contended with Amsterdam as a diamond-cutting center. The Brabant rosette, as Whitlock remarks, “represents an unsuccessful attempt to rival a characteristic Dutch cutting.” The very name of the Brabant rosette indicates its antiquity and early lapse from popularity. Brabant is the name of the historical region in northern Europe where the city of Antwerp belonged. This old duchy had broken into provinces, of which the central province no longer goes under the name Brabant. After Belgium gained independence in 1830, Central Brabant changed its name to that of the capital, Antwerp.

Half Dutch Rosette

Modified versions of both the Dutch rosette and the Brabant rosette bore much simpler cross facets. While the cutters kept the star facets and the cross facet beneath each, they left the remainder of the rose-cut diamond in large single facets, instead of dividing them into two cross facets.

The result bears a starkly prominent six-rayed star, consisting of a series of rhombs radiating from the center. This style of the rosette reduced the number of facets from 24 to 18.

Bauer from the 1800s relates that this modification occurred on the Brabant rosette, not the Dutch rosette. On this account, the name ‘half Brabant rosette’ was more appropriate for this variant of the rose cut. For some reason, however, the shape acquired the name ‘half Dutch rosette.’

Whitlock, writing in 1926, used no such name. The term probably came into use later on, long after the central province of Brabant no longer existed as such, but already went by the name Antwerp. In such circumstances, the nomenclature fell back on the Dutch rosette, instead of the word taken from the already inexistent name of a province.

Antwerp Rosette

In its simplest form, the rose-cut diamond consisted only of the hexagonal star and six more facets, each filling the space between the base of a star facet and the very edge of the gem.

This rose diamond thus resembled a two-tiered step cut without a table at the center. The substitution of small triangular cross facets with the large equilateral ones reduced the total number of facets to just twelve.

Whitlock believes this was the oldest form of the Dutch rosette, but Bauer from the preceding century describes the same design as a modification of the Brabant rosette. Having come from Antwerp in great number, this 12-faceted rosette became known as ‘Antwerp rosette.’

It is interesting to note that while the facets of a rose-cut diamond, whether of the Dutch or another sort, generally came in multiples of six, Antwerp roses were known for having less. King made mention of Antwerp roses displaying a total of only eight facets, along with those of only six.

Given the fewer facets, Antwerp roses were consequently less brilliant. Lapidaries generally resorted to this shape only when the rough diamonds were too small to admit of a full rose cut.

Rose Recoupee

Rose recoupee is a rose cut with twice more star facets than the regular rosette. This is similar in thickness to the Dutch rosette, but is peculiar in having twelve triangular facets, instead of six, constituting the star at the center.

Like the Dutch rosette, the recoupee has the bases of its star facets each touching the base of a cross facet to form rhombs. With a twelve-rayed star and consequently narrow star facets, the remaining spaces simply received a polish, as in the case of the half Dutch rosette, thus resulting in triangular facets around the edges of a twelve-sided gem. The additional 24 facets along the teeth give a total of 36 facets on the upper portion of the elaborate rose-cut diamond.

The recoupee far exceeded the other rose cuts in brightness. The steeper sides of this rose diamond brought the gem to a pyramidal shape of the ideal proportion. In consequence, there were less light leaking through the bottom of the rose-cut diamond. Most bounced off the base and shone through the surface.

Cross Rosette

A rosette that has plane lozenges for its star facets is the cross rose. Besides six, this very rare rose diamond also has facets in multiples of eight. It was the arrangement of eight rhombic facets that earned this rosette its name. Together the rhombs form a cross, hence the name ‘cross rosette.’

Unlike other rose cuts, long narrow facets along the edges of the rose-cut diamond typically completed the cross rosette.

Double Rosette

The bottom of a rose-cut diamond is not always flat, but may reproduce the entire faceted side of the Dutch rosette, thus forming two roses joined base-to-base. This shape is the double rosette. In this gem, the facets, which occur only on one side of the single rosette, appear over the entirety of the rose diamond. Triangular or rhombic planes thus cover the whole gem.

Double roses are particularly suitable as pendants for necklaces and drop earrings. Each rose-cut diamond is ideally set in a loop clasping the girdle.

Briolette

A modified form of the double rosette tapers toward one side. When the resulting outline takes the shape of a pear or teardrop, the rose-cut diamond popularly goes by the name ‘briolette,’ also rendered ‘brillolette,’ ‘brilliolette’ and ‘briolet.’ The name ‘briolette,’ however, also denotes the oval double rosette; thus, the more specific name ‘drop briolette’ was in use to mean the pear-shaped gem.

Popularity of the Rose-Cut Diamond

In consequence of its remarkable superiority to contemporary cuts — namely, the point and the table — the rosette spread rapidly after its introduction to Europe. Lapidaries extensively adopted the rose-cut diamond, which thus quickly became popular. Hence, large antique diamonds appeared in this shape.

From the 1600s to the first quarter of the next century, the rosette was the only well-known shape for diamonds besides the table. Thus, in the British jewelry of the reign of Queen Anne, the rose-cut diamond and the table alone appeared. The rose diamond in fact prevailed across Europe, until the discovery of the brilliant cut led to the former’s decline.

Decline of the Rose-Cut Diamond

As it turns out, the brilliance of the rose-cut diamond pales in comparison to that of the brilliant-cut. What was particularly lacking in the rose diamond was the dispersion of light into the colors of the rainbow. The ray of light that goes through one side of an inverted pyramid, which is essentially what the shape of the rosette is, comes out of the other side with its constituent colors parallel to each other, not bent and therefore separated. As a result, the rosette gives a virtually white brightness, lacking the colorful fire characteristic of a cleverly shaped diamond. On the contrary, such a beautiful play of colors comes out in the brilliant cut. As Tolkowsky concludes, “This is the fundamental reason of the unpopularity of the rose; there is no fire.”

Thus, although the rose-cut diamond gives out a strong brightness, this old cut does not bring the dispersive power of a diamond to fruition. In contrast, the brilliant cut, in the course of its evolution into the round brilliant, proved to be much brighter and more beautiful. Consequently, as Whitlock concisely states, “Since the 17th century the rose cut has steadily given place in popularity before the increased luster of each succeeding modification of the brilliant cut.”

Eventually, the brilliant overshadowed the rosette in popularity, and consequently in value. By 1750, a rose-cut diamond had only 3/4 the value of a brilliant, and by 1823 less than half the price an inferior brilliant of the same weight. The value of large rose diamonds, moreover, fluctuated and became quite unpredictable.

The rose-cut diamond became so unfashionable that the old diamonds underwent makeovers and became brilliants. Worse, people even forgot that ‘roses’ were diamonds too.

Survival of the Rose-Cut Diamond

Still, the old rose-cut diamonds did hold value as pieces of antique jewelry. Besides the table, the rosette came out as a reliable sign of a jewel’s antique origin. Moreover, the rose diamond enjoyed renewed interest near the last quarter of the 1800s. Owing to the rosette’s relatively low cost, which was half the price of brilliants then, many people took to buying and wearing rosettes.

Furthermore, while rosettes were quite out of fashion by the end of the 1800s, they still fetched 4/5 the price of brilliants of the same weight and quality in the beginning of the next century. The rose-cut diamond thus remained profitable, especially since its less numerous facets cost much less to polish.

Indeed, the rose cut remained in general use, and simply became second in importance to the brilliant. At this time the rosette was one of only two cuts in general use for diamonds. Thus, the diamond became the only gem so invariably shaped into either pattern that the stone was frequently referred to simply as either a ‘brilliant’ or a ‘rose.’

At this point, however, lapidaries reserved the rose cut for diamonds of smaller sizes. In fact, the ultimate reason this shape remained indispensable despite its plummeting popularity was the economy in waste that rose-cutting afforded for such a costly material. When rough diamonds stood to lose too much of their weight if they were to take the shape of a brilliant, cutters fell back on the good old rosette. When a rough stone would produce a large rose-cut diamond instead of a small brilliant, the rosette became more attractive.

Efficiency Sustains the Roses

The rosette was particularly suitable for a rough diamond too broad for its depth to efficiently admit of the brilliant pattern. When such a stone nonetheless received a brilliant cut, the result would be a shallow gem known as a ‘spread brilliant,’ to which the rose-cut diamond was still far superior in brightness and luster.

The rosette was so economical that rough diamonds subjected to brilliant cuts produced rose diamonds as byproducts. When cutters cleaved fragments off a large diamond to make a brilliant, they also carved the resulting lasques into roses. In this fashion, the rose-cut diamond became a byproduct of the brilliant, hence the former’s enduring general use, even as the rose diamond dwindled in popularity in favor of the brilliant.

Thus, diamonds too thin for brilliant cut became rose-cut diamonds, as did badly shaped and defective stones. Flat twinned crystals, which could not receive the brilliant pattern, likewise turned into rosettes. Hence, as late as the first quarter of the 1900s, flat pieces of rough or split diamonds became roses, chiefly in smaller sizes.

Still, as a rule, only small diamonds of trifling thickness, as well as large stones too shallow in proportion for a brilliant, were subject to the rosette’s pattern. Rough diamonds received this shape only when they were too small or too thin to make into brilliants.

Disappearance of the Rose-Cut Diamond

Unfortunately, for the rose-cut diamond to give the most brilliance, the gem has to be thick, as deep as the pyramid making up the underside of the modern brilliant. The thinner the rose diamond is, the more that light leaks through the base, thus leading to inferior brilliance. Cutters did have an idea of the optimal proportion that brings the most brilliance out of a rosette, which, as a rule, was half as deep as it was wide. Unfortunately, cutters ordinarily ignored this ideal proportion.

In actual practice, since cutters aimed for the least possible waste in raw material, the proportion of a rose-cut diamond depends largely upon the dimensions of the rough stones, which were mostly quite flat. As a result, rose diamonds were generally too thin for their breadths, and consequently less brilliant.

Eventually, even flat diamonds, when large enough, received the brilliant pattern, which results in several small brilliants instead of a single large rosette. The rosette became necessary only for very small diamonds, particularly those appearing in clusters. Today, with the aid of advanced technology, brilliants can be even smaller. The 20th century and beyond saw the affirmation of Tolkowsky’s opinion of the rose-cut diamond. “Fundamentally wrong,” says the Belgian engineer who unveiled the ideal proportions of the brilliant, “and should be abolished altogether.”

When mounted in jewelry, the rose-cut diamond, unlike the brilliant, was never set a jour. The lack of a pavilion renders an open setting for the rosette much too unsecure. The rosette’s thin edges are also too delicate to be left exposed. Jewelers thus fixed the rose diamond in a closed setting, to which the stone was even frequently cemented to keep it firmly in place.

The Rose-Cut Diamond Today

Today, though the rose cut remains in use, diamonds rarely receive such a cut. On the other hand, less precious stones, particularly those fashioned into beads, often bear the rhombic facets of the rose diamond.

Article published

Don’t miss a post about gemstones

Read them on your email

20 Spring Gems

Explore the gemstones that represent spring.

See All Diamond Cuts

Check the different shapes and patterns that bring out the beauty of diamond.

Check the important diamond cuts

- DIAMOND CUTS : 70 Choices of Diamond Shapes in History

- EMERALD-CUT DIAMOND : Popularity of the Rectangle Diamond

- CUSHION-CUT DIAMOND : Efficient Brilliance of Square Diamond

- PRINCESS-CUT DIAMOND : The Sharp Square Diamond

- IDEAL-CUT DIAMOND : Why the ‘American-Cut Diamond’ Endured

- ROUND BRILLIANT-CUT DIAMOND : Why Round Diamond Is Best

- TABLE-CUT DIAMOND : The Original Diamond Cut

- POINT-CUT DIAMOND : The First Diamond Cut?

- ROSE-CUT DIAMOND : The Face of Antique Diamonds

Know Your Birthstone

Tell us what you know