Diamond cuts sought to bring out the innate brilliance of a diamond. Skillful cuts of diamond bring the stone’s unrivaled brightness into conspicuous display, while the best diamond shapes make the most of the stone’s enormous ability to disperse light into the colors of the rainbow. Until the different types of diamond cuts unfolded the gem’s inherent brilliance and fire, people did not quite appreciate how beautiful diamond is.

Time to read:

Table of Contents

Evolution of Diamond Cuts

To make the gem shine and sparkle, lapidaries arrived at different diamond shapes and designs. These diamond cuts they developed from standards handed down from their predecessors, as well as their own lengthy experience. In a given diamond shape, moreover, cutters also discovered the proportion that unfolds the stone’s brilliance most effectively.

Consequently, while people in ancient times were content holding on to the octahedral shape of the rough crystal, there is now a variety of diamond shapes and patterns. Since this gemstone, like other transparent stones, is more brilliant when it bears facets, the different diamond cuts generally come with a number of plane surfaces.

These different shapes of diamonds came about rather slowly. In their quest to bring out the most of diamond’s beauty, lapidaries invented new types of diamond cuts and discarded old ones, with variants surfacing between the different types. Some of these cuts of diamond were so important that they determined the word with which the polished gems went by. Thus, a point, a table, a rose and a brilliant are all diamonds that went by the name of their cut. There is only one diamond shape, however, that proved to be the most prevalent, and that is the round brilliant.

1. Point: First of Diamond Cuts

The first known diamond to have been entirely polished into a definite shape was a point. There was in fact not much cutting to do on such a gem. The procedure consisted simply of polishing all the natural faces of the octahedral crystal. The result is a similarly deep gem, yet of quite a regular form. This diamond shape cleanly resembles two symmetrical pyramids joined at the base. The point stone indeed perfectly embodies the symbol of the suit of diamonds in a playing card.

TABLE DIAMOND CUTS

The second known diamond to have ever been cut was a table. Though the table cut was not original to the diamond, the table was the diamond’s original cut, distinct from the rough stone’s octahedral shape that the point cut simply rendered sharp and quite regular.

The table diamond itself was a variation of the point. The former merely modified the point by cutting off its opposite ends. Hence, tables were simply octahedral diamonds with cropped apices. The result, when viewed from above, is a gem of a square outline, sloping edges and a broad flat plane at the center. The word for this wide facet at the top is the ‘table,’ hence the name ‘table cut.’

Tables came in a range of variation. First, the table varied in the proportion between the depth of its crown and that of the pavilion. Furthermore, the introduction of additional facets modified the table. See also —

2. Typical Table

The typical table had the same depth above the girdle as it had below. The crown and the underside are thus exact replicas of each other, and the table at the top is as wide as the facet at the bottom.

3. Thin Stone

Lapidaries made thin diamonds into shallow tables, which Europeans called ‘thin stones.’ The cutters carved a bevel along the sides of the thin stone both above and below, thus producing a crown and a pavilion similar to those of the typical table, yet of such trifling depth.

4. Half-Grounded Table

When the bottom facet of the table stone is broader than the top, such a table is called ‘half-grounded.’

5. Thick Stone

As late as the early 1600s, table diamonds popularly had crowns that were thinner than their pavilion. To produce such a gem, cutters ground away the top end of the octahedral crystal much deeper than they did the bottom end.

6. Stepped Table

Cutters modified tables of different proportions — whether the typical table, thin stone or thick stone — by grinding the edges of their table facets into long narrow planes. These additional step-like facets on the crown augmented the brilliance and luster of the diamond.

7. Single Cut

The awkwardness of a square girdle led to another modification of the table. In this succeeding form, the facets of the table doubled in number. Instead of four sides as viewed from above, the outline of the table had eight, bringing the total facets to eighteen. Such a gem later acquired the name ‘single cut.’

8. French Cut

Whereas the earliest table diamonds were shaped from octahedral crystals, the French cut was fashioned from dodecahedral diamonds, or those having twelve faces instead of eight. The latter diamond cut roughly follows the same method as the former, with only the shapes of the raw materials deciding the difference between the finished gems.

Where the table cut truncates the apex of the octahedral diamond so as to leave behind the square table, the French cut crops the top rhombic faces of the dodecahedron by half, thus giving way to a similarly square table, but one that sits at the center of a four-rayed star.

ROSE DIAMOND CUTS

The rose cut takes the form of a pyramidal or hemispherical gem covered all over in small facets. Like a cabochon yet facetted all over, this diamond shape has all its facets on the upper side only, while the underside is simply flat, resulting in a broad plane forming the base of the gem. Also called ‘rosette,’ the rose earned its name from the fanciful comparison of its faceted dome to an opening rosebud.

With a diversity in the shapes of facets, their number and arrangement, the rose comes in a rather numerous varieties of diamond cuts, some of which readily identified the place whence the polished diamonds came. See also —

9. Dutch Rose: Once the Most Popular of Diamond Cuts

Unless otherwise specified, the rose refers to the Dutch Rose. What distinguishes this diamond shape from other rose cuts is its high pyramidal dome. As a rule, the Dutch Rose is half as deep as it is wide, thus conforming to the ideal proportion that brings the most brilliance out of the rose.

10. Brabant Rose

The Brabant Rose is similar to the Dutch Rose in the arrangement of its facets, but not in their angles and hence the proportions of the entire gem. The central facets of the Brabant Rose form a much lower pyramid, resulting in a rather rounded crown. The cross facets around the edges of this diamond shape also incline in a somewhat steeper angle, thus decidedly giving the gem a hemispherical profile.

11. Half Dutch Rose

Modified versions of both the Dutch Rose and the Brabant Rose bore much simpler cross facets. While the cutters kept the star facets and the cross facet beneath each of them, they left the remainder of the gem in large single facets, instead of dividing them into two cross facets. The resulting diamond shape bears a starkly prominent six-rayed star, consisting of a series of rhombs radiating from the center.

12. Antwerp Rose

In its simplest form, the rose consisted only of the hexagonal star and six more facets, each filling the space between the base of a star facet and the very edge of the gem. This is the Antwerp rose, a diamond shape resembling a two-tiered step cut without a table at the center.

13. Rose Recoupee

Rose recoupee is a rose with twice more star facets than the regular rose. This diamond shape is similar in thickness to the Dutch Rose, but is peculiar in having twelve triangular facets, instead of six, constituting the star at the center. With a twelve-rayed star and consequently narrow star facets, the remaining spaces simply received polish, resulting in triangular facets around the edges of a twelve-sided gem.

14. Cross Rose

Cross rose, or cross rosette, is a rose that has plane lozenges for its star facets. Besides six, this very rare rose also has facets in multiples of eight. It was the arrangement of eight rhombic facets that earned this diamond shape its name. Together the rhombs form a cross, hence the name ‘cross rose.’

15. Double Rose

The bottom of a rose is not always flat, but may reproduce the entire faceted side of the Dutch Rose, thus forming two roses joined base-to-base. This gem is the double rose. In this diamond shape, the facets, which occur only on one side of the single rose, appear over the entirety of the stone. Triangular or rhombic planes thus cover the whole gem.

16. Briolette

A modified form of the double rose tapers toward one side. When the resulting outline takes the shape of a pear or teardrop, the diamond cut popularly goes by the name ‘briolette.’

17. LASQUE AMONG DIAMOND CUTS

In extracting diamonds from beneath rocks, Indian miners inadvertently fractured the precious stones with the blows of their crowbars. When they found the diamonds thus flawed, the Indians set to work cleaving the stones to separate the good portions from the flaws. The resulting fragments generally become lasques.

Fragments cleft off a larger stone usually have a triangular outline, being parallel to the face of a native octahedron. However, Indian lapidaries gave the lasques other shapes. Around 1823, the lasques were broad flat rectangles, usually very thin. In the 1860s, this diamond shape was generally a flat, shallow parallelogram.

18. Beveled Lasque

Cutters also fashioned tables from lasques. However, since the latter were not thick enough for either the point or the full table, the thin diamonds merely became shallow reproductions of the table, exhibiting the broad crown above, but not the pavilion beneath the girdle. By carving a bevel along the sides, the cutter created the crown of this shallow diamond shape.

19. Portrait Cut

An enduring variation of the lasque is the portrait cut. This diamond shape first came into fashion in England in the late 1700s. Diamonds shaped in this manner served to cover portraits in jewelry, hence the name ‘portrait cut.’

Like the ordinary lasque, portrait stones consist of thin plates of diamonds evenly polished on both sides. The difference lies in the edges. Where other lasques simply had smooth edges or a bevel around the sides, the portrait cut has many tiny facets carved along its perimeter like the frame of a portrait.

20. MUGHAL DIAMOND CUTS

The Mughal cut of India came in various shapes and facets. Indian artists shaped diamonds into briolettes tapering on both ends, pear-shaped rose, rose with a pavilion, rose with a table, a brilliant shape with elongated facets, and more. The most famous of these diamond cuts was that worn by the historic Kohinoor before its recutting in Europe. The ancient gem resembled a regularly shaped volcano with a table in place of the vent, and long vertical facets cascading down its conical body.

BRILLIANT DIAMOND CUTS

The brilliant is famed as the crowning invention in the art of diamond-cutting. Known for its captivating effulgence, this diamond shape has been so fashionable that its shape has come to represent diamonds in general.

In essence, the round brilliant takes the shape of two cones sharing the same base, but with the apex of the upper cone cropped so as to leave a broad flat surface above, better known as the ‘table.’ The truncated upper cone becomes the crown of the gem, while the lower cone constitutes the pavilion.

21. Double Cut

The first brilliant went by the name ‘double cut.’ Also known as Mazarin cut, this diamond shape was a square brilliant. Its crown has sixteen facets surrounding a square table. The girdle echoes the shape of the table and accordingly produces a squarish outline, which earned this diamond cut the alternate name ‘square-cut brilliant.’

22. Brilliant-Top Table

By the 1800s, there were table stones that bore the crown of the double-cut brilliant, while the underside kept the original facets of the table.

23. Old English Star Cut

Known by various names — including ‘English square-cut brilliant’ and ‘English double-cut brilliant’ — the old English cut similarly has sixteen facets along the edges of the crown, but differs from the ordinary double cut in having an octagon for the table instead of a square.

24. Pentagon-Faceted Brilliant

A late version of the double cut embodies the turning point between the old double cut and the triple-cut brilliant. This diamond shape displays the octagonal table of the English star cut, yet the star facets surrounding the table are not triangles but pentagons. The edges between these pentagons extend from the table toward the girdle, thus dividing the triangular cross facets in two, which consequently received the name ‘half facets.’ The same facets occurred in subsequent versions of the brilliant.

25. Triple Cut

At the end of the 17th century, a new yet related diamond shape followed the double-cut brilliant. Stones fashioned in the novel diamond cut, known as the ‘brilliant recoupee,’ emerged from the city of Venice, which was the chief seat of the diamond trade in Europe at the time. Vincenzio Peruzzi developed the triple-cut brilliant, which had twice more facets on the crown. For this reason, the early triple cut also goes by the name ‘Peruzzi cut.’

With 32 facets around a broad table and 25 facets below, Peruzzi’s pattern was even more effective in bringing out the brilliance and fire of the diamond. The total of 58 facets made it easy for this diamond shape to supersede the double cut, especially for large and valuable stones. In consequence, by the 1800s, triple-cut brilliants were the most common of polished diamonds.

26. Old Mine Cut

In later brilliants, the squarish outline endured. This was particularly true of diamonds bearing the Old Mine cut, which acquired its name from the fact that the stones came from the old mines of Brazil and India. This diamond shape preserved the facets of the old triple cut, but reduced the depth of the gem to an extent that the crown and the pavilion meet at an angle rather close to that of the ideal round brilliant.

27. English Round Cut

The triple-cut brilliant did not stay in a squarish outline, but evolved to acquire a round shape. In mid-19th-century England, a round triple cut known as the ‘English round cut brilliant’ came into fashion. This diamond shape now goes by the name ‘Old English cut.’

28. Old European Cut

Mainland Europe produced brilliants similar to the English round-cut brilliants. However, the European diamond cut was reputedly less fine and weightier than necessary. To differentiate Britain’s round brilliant from those of mainland Europe, people called the former the ‘English round cut.’ Later on, in the same way that the English round brilliant acquired the name ‘Old English cut,’ the deep round brilliant from mainland Europe now also go by the name ‘Old European cut.’

29. Round Brilliant: Best of Diamond Cuts

While the squarish triple cut proved exceedingly dull for the diamond, neither did the thick proportions of both the English round cut and the Old European cut prove satisfactory. On the other hand, when the triple cut reached its perfection, the diamond shape became the round brilliant as we know it, bearing the faceting of the triple cut yet in a circular outline, thus symmetrical around an axis, and in just the right depth.

Given its superior brilliance, there is little wonder how the round brilliant rose to popularity, and prevailed since the 1700s over the squarish triple cut, which thus became the ‘old-cut brilliant.’ An excellent round brilliant is so effulgent that diamonds of other cuts appear dull and lifeless in comparison.

In 1919, an engineer explained through physics how the round brilliant was indeed the most beautiful of diamond cuts. Marcel Tolkowsky discovered the exact proportions that achieve an optimum balance between reflection and dispersion of light in a brilliant-cut diamond, and these were found in the round brilliant.

Round brilliants did not invariably have the same number of facets. In general, the name ‘brilliant’ refers to the complete diamond shape, better known in the 1800s as the ‘thrice formed brilliant.’ This round brilliant is the perfect, most complex form and consequently the most valuable. Indeed, what distinguishes the thrice-formed brilliant from the other diamond cuts is its complete set of facets, at least a series of which the less valuable brilliants lacked. See also —

30. Once-Formed Brilliant

While the once-formed brilliant keeps the star facets surrounding the broad table at the center, this lesser diamond shape lacks the divided cross facets bordering the edges, both on the upper and lower side of the gem. The main skill facets on the crown and around the pavilion were simply ground until they meet at the girdle.

31. Twice-Formed Brilliant

Like the once-formed brilliant, the twice-formed also lacked cross facets, but only at the top. The pavilion keeps the ring of triangular half facets just beneath the girdle.

32. Table-Cut Brilliant

A shallow round brilliant that lacked both the star facets and the divided cross facets along the edges was the so-called ‘table-cut brilliant’. This diamond shape is obviously simpler to manufacture. Out of the 58 facets of the full brilliant, the table-cut brilliant displays only 33.

33. Brillonette

Occasionally Europeans met with a half brilliant, also known as ‘brillonette’ or ‘brillonet.’ While this diamond cut displayed the crown of a brilliant, it lacked the pavilion beneath. Indeed, like a rose, the brillonette had nothing below the faceted crown but a large flat face.

Cutters resorted to this rare diamond shape when the rough stone was too thin to make into a full brilliant. A gem so shaped, however, is far inferior in brightness to the complete brilliant.

34. Ideal Cut

A brilliant that conforms to the ideal proportions that Marcel Tolkowsky unveiled now go by the name ‘ideal cut,’ alternately rendered the ‘American ideal cut’ and ‘Tolkowsky brilliant.’ When accurately executed, the best proportions of this diamond shape result in the most beautiful gem, exhibiting the greatest refulgence.

35. Star Cut

An interesting spin on the round brilliant came at the beginning of the 19th century, when a Parisian jeweler called Caire devised a round cut that minimizes the waste in rough material. While the crown of this diamond cut simply presented the facets of the brilliant in quite a different set of proportions, the underside introduced slight modifications to the same shape. The resulting diamond shape ultimately looked quite different, both above and below the girdle. The gem displayed an unmistakable star at the center of the crown, while a huge Star of David appears on the pavilion. Both stars evidently earned this diamond shape the name ‘star cut.’

The star cut combined the efficiency of the rose with the superiority of the brilliant. The star cut thus resembled entire pyramids joined base-to-base and truncated but sparingly on both ends. When subjected to this diamond cut, the rough stone loses but little of its weight, yet achieves the brightness of the ordinary brilliant.

36. Hearts and Arrows

The best form of the round brilliant is now widely reputed to be the so-called ‘hearts-and-arrows.’ In addition to the ideal proportions of the brilliant, the hearts-and-arrows diamond exhibits precise symmetry of facets that when viewed through a specialized equipment, known as Hearts and Arrows scope, produce the appearance of arrows on the crown and hearts on the pavilion.

37. Leonardo Da Vinci Cut

A quirky take on the round brilliant is the Leonardo Da Vinci cut. For the dimensions of its facets this diamond cut observes the golden ratio or 1.618:1, which became popular from the works of the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. The resulting diamond shape is a round brilliant showing a large pentagram on the crown, as well as a small five-rayed star at the bottom, whence the star radiates with quite longer facets right to the edges.

Fancy Diamond Cuts of the Brilliant Pattern

Although most popularly round, the brilliant is not always circular. In the course of its evolution, this diamond cut took on different shapes. In the 1800s particularly, cutters largely depended upon the natural shape of the diamond in deciding the overall outline of the polished gem. When the round brilliant appeared to be inefficient for a rough stone, cutters chose a diamond shape that approximates to the form of the raw crystal. Such fancy brilliant was manufactured rather frequently, particularly for solitaire rings and as the center of clusters.

38. Cushion Cut

Conspicuous among the fancy brilliants is the cushion cut. The most efficient diamond shape is square, since this is the natural outline of the octahedral crystal. The cushion cut follows this square outline, which accordingly gives this diamond cut a squarish girdle. See also —

39. Oval brilliant

When the rough stone is elongated in one direction, the diamond is more efficiently shaped into an oval than a round brilliant. The oval brilliant follows the faceting of the round brilliant, complete with a crown and a pavilion, except that both parts of the diamond shape are elongated on two opposite sides.

40. Trilliant

Another fancy shape for a brilliant is the triangle. This diamond shape varies from a sharply angular triangle with straight sides to one with a convex outline, giving the gem a shield-shaped girdle.

41. Pear Brilliant

Formerly known as the ‘pendent cut,’ the pear-shaped brilliant has the outline of the diamond shape elongated and tapered toward one side until the gem terminates in a point.

42. Marquise

While the pear shape terminates in a point on one end of the elongated gem, the marquise terminates in a point on both ends. The 58 facets of the typical marquise correspond to those of the round brilliant, but differ in actual shape in order to accommodate the elongated outline of this diamond shape.

43. Heart Brilliant

Intimately related with the pear is the heart-shaped brilliant. The heart brilliant may in fact be considered as a pear brilliant of distinct proportion, where the diamond shape is about as broad as it is long.

44. Pendeloque

The pendeloque takes the pavilion of the brilliant, and also reproduces it above the girdle in place of the truncated crown. Thus, the pendeloque has no table; instead, the crown of this diamond cut continues to taper toward a point at the top, just as the pavilion tapers toward a point at the bottom. The resulting diamond shape consists of two cones joined at the base, and completely faceted on all sides.

45. Twentieth-Century Cut

Pendeloque comes in more elaborate variations, including the one called ‘twentieth-century cut.’ The latter diamond shape has eight star facets around the apices of both the crown and of the pavilion. The facets total 80, with 40 above and 40 below the girdle.

46. Double Brillonette

Not all circular, oval or teardrop-shaped gems faceted on both sides are double roses. One would find in today’s market double-cut stones, often drilled as beads, with a large flat face at the center of each side. Instead of the rose’s, these gems reproduce the brilliant’s crown, with its broad table surrounded by skill facets. Still, only the brilliant’s crown is reproduced; on the underside, in place of the pavilion is a copy of the crown. Basically a double brillonette, this diamond shape consists of two brilliant crowns joined base-to-base like a double rose.

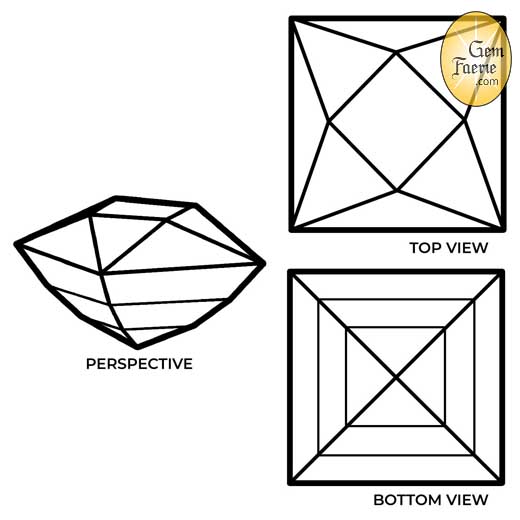

47. Princess Cut

Princess cut is a square pattern that makes full use of the square outline of the octahedral crystal, thus leading to minimal waste in rough material. What chiefly distinguish this diamond shape from the cushion cut are the corners. Unlike the cushion cut, the princess cut has sharply square corners. See also —

48. Sakura Cut

Similar to the Da Vinci cut in having a pentagonal table is the sakura cut of Japan. Unlike the former, however, the sakura cut has a strikingly broad table, around which the facets unfold like the petals of the sakura or cherry blossom, which inspired this diamond shape. The pavilion, on the other hand, consists simply of long thin vertical facets, meeting at a ten-petalled flower at the center. Unlike the classic round brilliant, the overall outline of a sakura-cut diamond is a decagon, whose ten sides are quite straight.

49. STEPPED DIAMOND CUTS

Also known as ‘trap cut,’ step cut is a style formerly applied only to colored stones. As viewed from the top, this diamond cut takes the shape of a polygon, particularly one that has four, six or eight sides. Hence, the step cut may be square, a hexagon, or an octagon. Sometimes, this diamond shape had twelve sides.

50. Carre Cut

Carre diamonds bear the most basic form of the step cut. Like the table, the carre cut consists of square pyramids joined together at the base with the upper apex truncated. This diamond cut indeed closely follows the shape of the octahedral crystal, thus leading to minimal waste in rough material.

However, being square with sharp angles, uncropped as in the emerald cut, the carre diamond is liable to chip at the corners. To preserve the gem from fracture, the mounting has to clasp the diamond by the corners, and thus protect these parts from external impact at the same time.

51. Emerald Cut

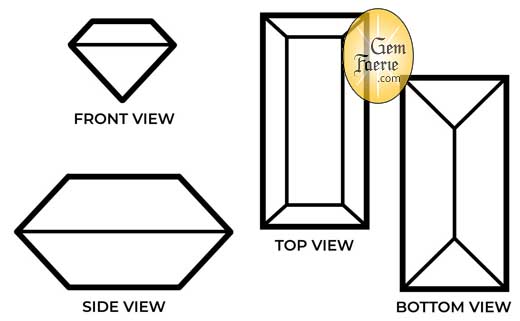

An emerald-cut diamond is a step-cut gem of a popularly rectangular shape, whose cropped corners prevent fractures. The result is an eight-sided diamond shape exhibiting short sides at the corners of a rather rectangular outline. See also —

52. Asscher Cut

The Asscher cut is a square pattern similar to an emerald cut, but bearing subtle differences from the latter diamond shape. An Asscher diamond can have deeply truncated corners, giving the gem an outline closer in appearance to an octagon than a square. Compared to the traditional emerald cut, the Asscher cut also has a higher crown, smaller table and deeper pavilion.

53. Hogback

An old shape that produced thin long diamonds went by the name ‘hogback.’ Popular from mid-1500s to the 1600s, such slender diamonds formed letters in jewelry. A hogback diamond took shape when the octahedral crystal was cleft in two, and the half cleft again along an edge of the octahedron, thus spanning its breadth. Viewed from the side, this diamond shape bears the rhombic outline of the octahedron.

54. Baguette

Derived from the hogback, baguette came into fashion from as early as 1926. This diamond shape consists of a long slender gem, hence its name ‘baguette,’ from the French for “small jewel.” The baguette took shape upon the application of the table cut on the hogback. To be specific, the cutter ground off the apex of the hogback to make way for the table.

55. MIXED DIAMOND CUTS

There are diamond cuts that combine the brilliant and the step cut in one gem. Such cuts are generally suitable for stones of a pale color. The most prevalent of these different cuts of diamonds are those that put together the crown of the brilliant and the pavilion of the step cut.

56. Brilliant-Top Cut

The best-known of mixed diamond cuts retains the crown of the brilliant, hence its alternate name ‘brilliant-top cut.’ Unlike its crown, the pavilion of this diamond shape adopts the horizontal facets of the step cut, thus tapering in a succession of step-like planes toward a point at the bottom.

57. Maltese Cross

The brilliant-top cut is not limited to a round outline. The mixed pattern may also be octagonal in shape. The diamond shape would then display the crown facets of a modified brilliant, where, instead of the cross facets along the girdle, the large facets between the star and cross facets are divided in two. The arrangement of facets on the crown somewhat resembles a Maltese cross, hence the name.

58. Hexagonal Mixed Cut

Besides an octagonal outline, the mixed pattern may also be hexagonal in shape. Here the four-sided facets of the brilliant’s crown are almost triangular. As in the Maltese cross, the fact that the brilliant’s facets on the crown are modified makes this diamond cut more consistent with the step cut, and therefore more closely related to the latter than to the brilliant.

Unless carefully proportioned, a diamond of a hexagonal mixed pattern loses much of its brilliance. This was probably the reason why only a limited number of diamonds received this pattern. Though accordingly often met with in old jewelry, this diamond shape later gave way almost entirely to various forms of unmodified step cut.

59. Stepped French Cut

The French cut is interesting in starting out as what was essentially a variety of the table and later morphing into what Whitlock called the ‘French cut brilliant,’ which is a mixed pattern with a square outline. While the original French cut had a simple inverted pyramid for its lower portion, a modified version of this diamond cut replaced the simple four-faced pavilion with step facets. Hence, by the 1920s, parallel horizontal lines made up the underside of the French cut, thus turning the diamond shape into a step cut below the girdle.

60. Double-Faceted Mixed Cut

The mixed cut with double facets is similar to the brilliant-top cut except that an edge appears along the bevel of the crown halfway between the table and the girdle, thus dividing the large rhombic facets of the brilliant top in two. This diamond cut also makes use of the brilliant’s half facets, the edges between which continue from the girdle to the bottom, thus doubling the vertical edges of the pavilion. This diamond shape is no more effective than the simple brilliant-top cut, and was simply availed of to remove or conceal flaws in the rough stone.

61. Mixed Cut with Elongated Facets

Fundamentally similar to the mixed pattern with double facets is one with elongated brilliant facets, particularly through the display of divided rhombic facets. The latter diamond shape differs in the length of the crown facets, some of which are longer and others shorter. The result may take the shape of a squarish gem, or one that is oblong in outline. This diamond cut also keeps the pavilion less busy by limiting its facets to eight columns.

62. Tiered Brilliant-Top Cut

Another hybrid between the brilliant and the step cut multiplies the brilliant’s crown facets into two rows or even more, while keeping the pavilion in layers of step facets. The overall outline of this diamond shape may be oval or oblong. An oval shape results from carving the facets in multiples of ten instead of eight, which is otherwise enough for oblong gems or rectangular jewels with rounded corners.

63. Radiant Cut

The radiant cut is a combination pattern of a typically rectangular shape. Truncated corners give this otherwise rectangular gem eight sides. A row of step facets border the edges, while a series of triangular facets, akin to those of a brilliant, extends from the step facets. Though not as bright as the round brilliant, the radiant pattern is famous for producing the most brilliance out of all the angular diamond cuts.

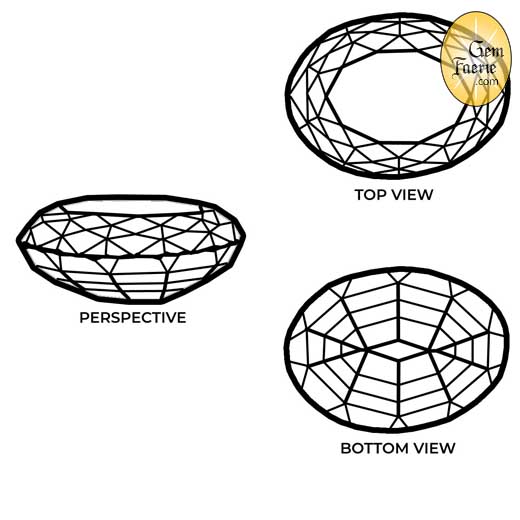

64. CABOCHON DIAMOND CUTS

Though diamond, as a transparent stone, is generally faceted, there were instances when diamonds were given rounded polished surfaces, and thus shaped en cabochon. Also known as ‘convex cut,’ cabochon is a popular shape for colored stones, but is also sometimes used on the diamond. From the Latin caput, meaning “head,” a cabochon is a hemispherical gem whose surface is polished but not faceted. When this convex gem displays a flattish top, the stone is said to be ‘tallow-topped,’ from its resemblance to a drop of tallow.

65. Double Cabochon

When a cabochon gem receives outwardly curving surfaces both above and below, its form is the so-called double-convex, formerly known in the English trade by the name ‘tallow-drop.’ In this shape, the upper dome typically arches higher than does the lower portion. Sometimes the edges and the underside bear facets. Today, such a form simply goes by the name ‘double cabochon.’

66. BEADS AS DIAMOND CUTS

There were rare instances when diamonds were bored through as beads. The term ‘beads’ in jewelry used to refer particularly to drilled small gems of symmetrical shape. When not covered all over in facets, beads are polished into spherical gems.

67. Rhomb-Faceted Beads

A very old design for beads makes use of the rhombic facets of the rose, as well as the long facets at the top and the bottom of the briolette. The gem thus resembles a rounded briolette.

68. Square-Faceted Beads

An unusual pattern for round beads consists of squarish facets, arranged in a matrix all over the stone. The horizontal alignment of facets resembling that of the step cut elicited the name ‘stepped bead’ for this design.

69. Hexagon-Faceted Beads

Another shape in which the facets of beads were formed was the hexagon.

70. FANCY DIAMOND CUTS

Fancy diamond cuts are done on irregularly shaped stones, including twinned crystals. The macle is indeed often the subject of a fancy diamond cut that simply renders the flat triangular shape of the twinned crystals more regular.

Fancy cuts of diamond in fact came in an extremely wide range. In these shapes of diamonds, there appears to be no set rule, and the resulting facets come down to the individual taste of each lapidary.

BEST DIAMOND CUTS

The job of a diamond-cutter is to carve a rough diamond into the most perfect symmetrical gem while preserving as much of its size as possible. A diamond shape that achieves these considerations becomes the most desirable.

However, it is not enough that a jewel comes in the best pattern and excellent proportion. The shape of the gem has to be quite regular too, and its facets symmetrical. The execution of the diamond cut and its proportion has to be precise.

Another consideration in choosing from among the different diamond cuts and shapes is the cost. The higher the number of facets is, the more costly a diamond cut is. Given how valuable the stone is, however, complicated diamond shapes with numerous facets are justifiable for the gemstone, since its value repays the high cost of labor-intensive cutting.

Article published

Don’t miss a post about gemstones

Read them on your email

20 Spring Gems

Explore the gemstones that represent spring.

Check the important diamond cuts

- DIAMOND CUTS : 70 Choices of Diamond Shapes in History

- EMERALD-CUT DIAMOND : Popularity of the Rectangle Diamond

- CUSHION-CUT DIAMOND : Efficient Brilliance of Square Diamond

- PRINCESS-CUT DIAMOND : The Sharp Square Diamond

- IDEAL-CUT DIAMOND : Why the ‘American-Cut Diamond’ Endured

- ROUND BRILLIANT-CUT DIAMOND : Why Round Diamond Is Best

- TABLE-CUT DIAMOND : The Original Diamond Cut

- POINT-CUT DIAMOND : The First Diamond Cut?

- ROSE-CUT DIAMOND : The Face of Antique Diamonds

Know Your Birthstone